Visit our blog to have a glimpse of how the regional elites on the northeastern periphery of the Habsburg Monarchy conceptualised the French Revolution as it developed before their eyes in the 1790s.

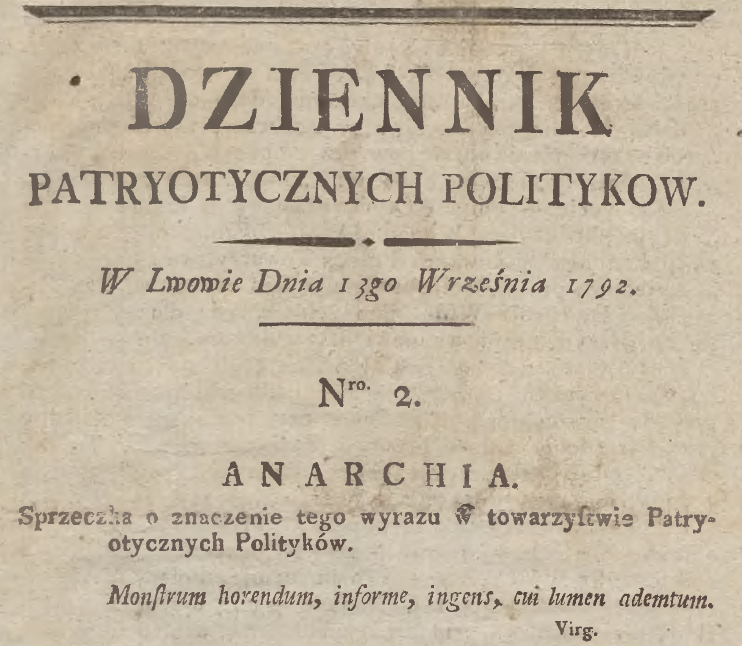

In the 1790s Mykhailo Harasevych, the patron saint of this research project, was involved in the publication of Galicia’s first political daily, the Dziennik Patriotycznych Polityków (Journal of Patriotic Politicians, henceforth DPP), allegedly a mouthpiece of the eponymous Towarzystwo Patriotycznych Polityków (Society of Patriotic Politicians). 1 Of the latter we know close to nothing (were they really a group of people or just a literary device?). The exact scope and nature of Harasevych’s contribution is yet to be ascertained, but it seems justifiable to assume that the ideological positions presented by the anonymous author(s) of this paper could not be very far from his own at that time. In any case, articles in the DPP show us what Galician elites knew about and understood from the European politics of the Age of Revolution and how they positioned themselves in regard to them as both the Austrian subjects and the former citizens of the still existing Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. 2 I have resolved to translate some interesting excerpts from the DPP as an illustration of the ideological horizon of Galician elites, be they Greek or Latin Catholic.

In the second issue of the DPP, released on September 13, 1792, we find an allegorical essay on anarchy, introduced as a discussion that allegedly took place at a meeting of the Society of Patriotic Politicians. The subject of anarchy was especially relevant in the early 1790s, as many enlightened Europeans observed the violent breakdown of the French monarchy with horror. Indeed, the very first issue of the DPP related in detail la journée du 10 août, when the republican fédérés stormed the Tuileries Palace, effectively ending the royal power. 3 However, the author of the DPP essay on anarchy chooses to articulate his reflection in a bipolar field. Along the rather obvious French context, the other crucial point of reference is the political scene of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: the conflict over the May Constitution of 1791 ending with Russian intervention and the creation of a reactionary government dominated by the so-called Targowica Confederation. 4

The text contains several interesting moments, but I would only like to draw readers’ attention to three points here. First of all, the participants in the discussion related in the essay do not hesitate to identify the inhabitants of Poland-Lithuania as their compatriots (Polish współziomkowie), yet they do not reveal any sense of special solidarity resulting from this fact. Although the Patriotic Politicians are visibly concerned about the fate of the Commonwealth, one can also sense a sort of satisfaction at Galicia’s splendid isolation from the chaotic Polish-Lithuanian factionalism. Secondly, the critique of the violence and instability allegedly inherent in republican politics, be it French or Polish-Lithuanian, is completely divorced from Catholic orthodoxy. 5 Some images seem to be inspired by the apocalyptic visions of the Francophone Counter-Enlightenment, but others come from the Masonic repertoire. As a whole, the argumentation in the essay is purely pragmatic and secular (or deistic, to be precise). The authors of the DPP do not align themselves with the radical enemies of the Revolution, but rather assume the position of a moderate conservative Enlightenment, not unlike the luminaries of the Austrian legalistic monarchism such as Leopold II himself, Joseph von Sonnenfels, or Karl Anton von Martini. 6 Lastly, it is striking that the authors’ political concerns are so much in line with those of their contemporaries from other parts of Europe. If not for the explicit references to Poland-Lithuania, one might not guess that this text was written and published in a country located to the east of the river Elbe. There is nothing fundamentally East European about its form and content.

Galician Patriotic Politicians prove to be keen observers of the European politics. They successfully synthesise their knowledge of Western and Eastern European developments into a coherent, if not very original, diagnosis of contemporary ideological conflicts. English civil wars, the French Revolution, May Constitution, and the Targowica Confederation are presented as items of the same series that could be captioned ‘republican disorders’. In this way, the Patriotic Politicians define their own location in a Lviv suspended between Paris, Vienna, and Warsaw. One cannot resist noticing that they seem to be quite satisfied that the House of Austria potects their Galician patria from the vicissitudes of republican factionalism. Here, we can see how a section of the Enlightened Polish-speaking elite of that Habsburg crownland, a country just twenty-years old at the moment, comes to terms with the dynamic realities of their time and thus contributes to the collective effort of inventing Galicia, a process analysed among others by Larry Wolff and Miloš Řezník. 7

*

ANARCHY

A quarrel over the meaning of this word in the Society of Patriotic Politicians

Monstrum horendum, informe, ingens, cui lumen ademtum.

Virg. 8

As is widely known, in accordance with the regulations adopted once and for all in our society, each member cum voce activa is responsible for one kingdom and has to faithfully gather news from that state, add his remarks, and pronounce his opinion during sessions in pleno, after which everybody is allowed to reveal their thoughts and say whatever they like. 9

When the reading of news at our last session was over, Mr. Zawieruchowski, 10 rapporteur of tidings from Poland, rose and spoke from the depths of his heart:

‘Thank God that peace has been restored in Poland. The way in which the unrest was quelled was onerous indeed, but as there was no other, they had to resort to this one. It is enough that the country is peaceful, that the war is over.’ 11

‘I am happy for you, sir,’ responded Mr. Mędrski, the serious president of our society, 12 ‘but I am still concerned about the future.’

‘But why?’ said Mr. Zawieruchowski. ‘Do you, sir, want the war to last longer?’

‘I despise the spilling of innocent blood, but…’

‘What are you afraid then? And what is the cause of your fear?’

‘Knowing how restless the minds of our compatriots are, do not I have legitimate reasons for concern about the future?’

‘It has always been this way: dilemmas, dissensions, hatreds often prove beneficial for a free country. Otherwise, would the Englishmen have brought their affairs to the present state?’

‘English history is full of dreadful periods. Moreover, do you deem, gentlemen, that Poles are Englishmen?’ 13

‘Why not? But this is a topic for another occasion. Now, sir, please tell us why you fear about the future.’

‘This is why: the sympathisers of the May 3 Constitution have not abandoned their hopes. Gentlemen, you heard recently that the number of the discontented is substantial and that the Friends of the Constitution will find supporters and backing for their endeavours.’ 14

‘So what?’

‘The General Confederation and its Protectress will not make any concessions.’ 15

‘What then?’

‘A civil war.’

‘And the outcome?’

‘The lot of Poland is pretty similar to that of France: anarchy! Oh, my beloved gentlemen, this word is dreadful, but its consequences are even worse: disgusting devastations!’

‘Please instruct me what this anarchy means. I hear this word a lot, but each person explains it in a different way.’

‘Sir, think about France and you will have a vivid representation of anarchy. All civic bonds are torn, government – toppled, laws – disrespected. Superiors are powerless, courts of law – deprived of authority, virtuous citizens – either murdered or moaning in dungeons, government – in the hands of the dissolute populace. A couple of days ago, after having read a lot about the current revolution in France, I fell soundly asleep and just before the dawn I had the following dream, as if I had been awake:

DREAM

I was near Paris, on Montmartre hill. 16 The land was covered in thick darkness and there was no light except for the moon beams. Suddenly, I noticed some divine figure approaching me from the east. It was adorned with brightness and the whole world was depicted on its vestments. From its pleasant face I recognised that this was Oromazdes (principium boni) floating on clouds above the unfortunate France. 17 When he came closer, I heard these words come out from his mouth: “The French nation is numerous, manly, industrious, and valiant, but lest it waste these rare gifts, I shall create a powerful genius to watch over its prosperity.” Then, he said: “Let it be so!” and immediately a female figure of such beauty appeared that I had never before seen an equal. Then, he took from the mass of farmers, artisans, and merchants and used this material to mould this woman’s breasts, which produced ambrosia instead of milk. Next, he took from the mass of learned men, statesmen, lawyers, and sages and having created a brain out of it he put it in her head, after which her eyes started to radiate with bright rays. Eventually, he took from the mass of kings and put it right in the middle of her brain saying: “This will be the centre where all the powers animating the limbs meet.” Immediately, the goddess began to move and act as a protectress of France. Oromazdes flew towards the west and I prostrated myself, piously adoring the omnipotence of gods.

Then, having heard the murmur of thunders in the distant north, I bounced to my feet. Again, there was a thick darkness interrupted by occasional lightnings. Trembling with fear I recognised the approach of Ahriman (principium mali), thunderbolts still in his hand. 18 “Hah,” he shouted in a tremendous voice. “The destroyer of my projects, that friend of good order, was here. I can see the traces of his actions. You, woman, are a work of his hands. True, you are powerful, but you will not be stronger than I am. Become what I want you to be!” Having said that, he threw a thunderbolt with his right hand and hit her right in her head: her eyes dimmed, her brain leaked, her breasts dried, and her limbs fell off. The whole body melted into an amorphous lump, which, too feeble to stand on its own, fell upon France. Her breasts teemed with worms and vipers; spears, swords, and daggers punctured her belly; and terrifying flames gushed from her intestines as if from a bottomless abyss. Having concluded this terrible work, Ahriman roared in the air: “Anarchy!” and flew back towards the north, whereas the terror woke me up.’

The whole society agreed to publish this dream in our journal. 19

⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻

1 See Maurycy Dzieduszycki, “Przeszłowieczny dziennik lwowski,” Przewodnik Naukowy i Literacki, Year 3 (1875), 33-51 and Halina Kozłowska, “Lwowski »Dziennik Patriotycznych Polityków« (1792-1798),” Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Prace Historyczne, No 55 (1976), 79-111.

2 Galicia was created as a result of the first partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772. The latter survived as a separate polity until the third partition in 1795. For 23 years the Commonwealth was Galicia’s northern neighbour and many noble landowners would have their land estates on both sides of the border as the so called sujets mixtes with the right to vote in the diets of both countries.

3 On August 2, 1792, radical republican militants, mostly the federés volunteers, stormed the Tuileries Palace, the Parisian residence of the royal family. This event resulted in the de facto end of constitutional monarchy in France (although the Republic was not officially proclaimed until the second half of September). In the following month French political scene became especially brutal and volatile, which is sometimes characterised as the First Terror. These events were widely publicised all over Europe, usually in a negative light.

4 In the eighteenth century the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth languished under Russian protectorate, as St Petersburg blocked any attempts at substantial political reform. The situation changed in 1787, when the Ottoman Empire declared war against Russia. Forced to focus on the military actions in the Black Sea region, Empress Catherine II was no longer able to control the Polish-Lithuanian politics so closely. As a result, years 1788-1792 saw intense political reforms in Poland-Lithuania, culminating with the Enlightened Constitution of May 3, 1791. However, many conservative republicans were unhappy with the new form of government: they deemed that it deprived them of their liberties for the sake of orderly administration. These malcontents formed in 1792 an oppositional union which went down in history as the Confederation of Targowica, named so after the town of Torhovytsia in central Ukraine, where its manifesto was allegedly penned and published. At the same time, Catherine signed a satisfactory peace treaty with the Ottomans and directed her gaze towards the Commonwealth. Thus, the Targowica leaders obtained the Russian military support necessary to overthrow the reformist government in Warsaw. The Russian invasion in the summer of 1792 brought an abrupt end to the period of Enlightened reform in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and accelerated the eventual collapse of this polity. The name of Targowica remains a byword for high treason in contemporary Polish.

5 For the Counter-Enlightenment see Darrin McMahon, Enemies of the Enlightenment: The French Counter-Enlightenment and the Making of Modernity (Oxford, 2001) and Martyna Deszczyńska, Polskie kontroświecenie (Warsaw, 2011).

6 See Teodora Shek Bernardić, “Modalities Of Enlightened Monarchical Patriotism In The Mid-Eighteenth Century Habsburg Monarchy,” in Balazs Trencsenyi and Márton Zászkaliczky, eds, Whose Love of Which Country? Composite States, National Histories and Patriotic Discourses in Early Modern East Central Europe (Leiden, 2010), 629-661.

7 Miloš Řezník, Neuorientierung einer Elite: Aristokratie, Ständewesen und Loyalität in Galizien (1772-1795) (Frankfurt am Main, 2016) and Larry Wolff, The Idea of Galicia: History and Fantasy in Habsburg Political Culture (Stanford, 2010).

8 A corrupted quote from Virgil’s Æneid. The correct version is Monstrum horrendum, informe, ingens, cui lumen ademptum, meaning: “A monster frightful, formless, immense, with sight removed.” It is a description of cyclops who were presented as quintessentially irrational and cruel brutes in the Greco-Roman poetry. Here, it serves as a metaphor of mob rule.

9 Cum voce activa literally means “with active suffrage,” but here it is probably intended to describe full suffrage. Sessions in pleno are general meetings, which all the members of the society are encouraged or even required to attend.

10 Mr. Zawieruchowski is a meaningful name derived from the Polish noun zawierucha, meaning storm, turmoil, chaos.

11 At the end of July 1792, in the face of overwhelming Russian might, Poland-Lithuania’s pro-reform king chose to surrender and accept the repeal of the 1791 Constitution. Targowica leaders took up the reins of government and started to persecute their enemies. In 1793, they had to swallow the second partition of the Commonwealth by Prussia and Russia, but until the outbreak of the Kościuszko Uprising in 1794 one could also credit them with providing a modicum of stability.

12 Mr. Mędrski is another meaningful name, this time derived from the Polish adjective mądry, meaning wise.

13 The authors mean here the British Civil Wars of 1638-1652 and the Glorious Revolution of 1688-1691.

14 By Friends of the Constitution the author may mean the members of the Assembly of Friends of the Government Constitution “Let there be Light” (in Polish Zgromadzenie Przyjaciół Konstytucji Rządowej “Fiat Lux”), sometimes credited as the first modern political party in Poland-Lithuania. More broadly, the author can describe in this way any supporters of the 1791 Constitution or in fact any enemies of the Targowica regime established thanks to the Russian invasion of 1792.

15 The General Confederation stands here for Targowica. Obviously, its protectress was the Empress Catherine II of Russia.

16 The hill of Montmartre remained outside the city limits until 1860.

17 In the Zoroastrian tradition Oromazdes (or Ahura Mazda) is the benevolent creator god, lord of wisdom and order, the hypostasis of good, rendered here in Latin as principium boni. Zoroastrian-inspired symbols were present in the Masonic rituals and, as a result, in the wider cultural sphere of the eighteenth-century Europe: see for example Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera Zoroastre (1756) about the struggle of good and evil spirits and their human followers.

18 In the Zoroastrian tradition Ahriman (or Angra Mainyu) is the hypostasis of evil, rendered here in Latin as principium mali, the destructive and chaos-sowing opponent of Oromazdes.

19 I would like to thank Jared Warren for his careful reading of the first draft of this translation and his useful editing suggestions.

⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻

This is not an academic text sensu stricto. Its goal is to disseminate knowledge and to stimulate public interest in our field. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of either PAN or NCN.

Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies releases a new collective volume on various Eastern Christian communities in the Austrian Monarchy. Edited by J.-P. Himka and F. A. J. Szabo, it features contributions from P. R. Magocsi, B. Puskás, and A. Zayarnyuk.

Learn more here.

A new collection of articles on the Synod of Zamość has been released in Polish under the editorship of Przemysław Nowakowski CM. Especially exciting is the contribution of the late Ihor Skochylias.

Learn more here.

First Conference of the Ukrainian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies will start in Lviv on 23 June. The event features Richard Butterwick, Penelope Corfield, Zenon Kohut, Volodymyr Sklokin, and Larry Wolff. There will be several panels on the Greek Catholic Church. All lectures and discussions will take place on ZOOM. For more info visit the website of the Humanities Faculty of the Ukrainian Catholic University.

Visit our blog to learn about the time when Warsaw was a town on the Austrian border. It makes it one of only four European capitals that had (or still have) their urban territory shared by two states.

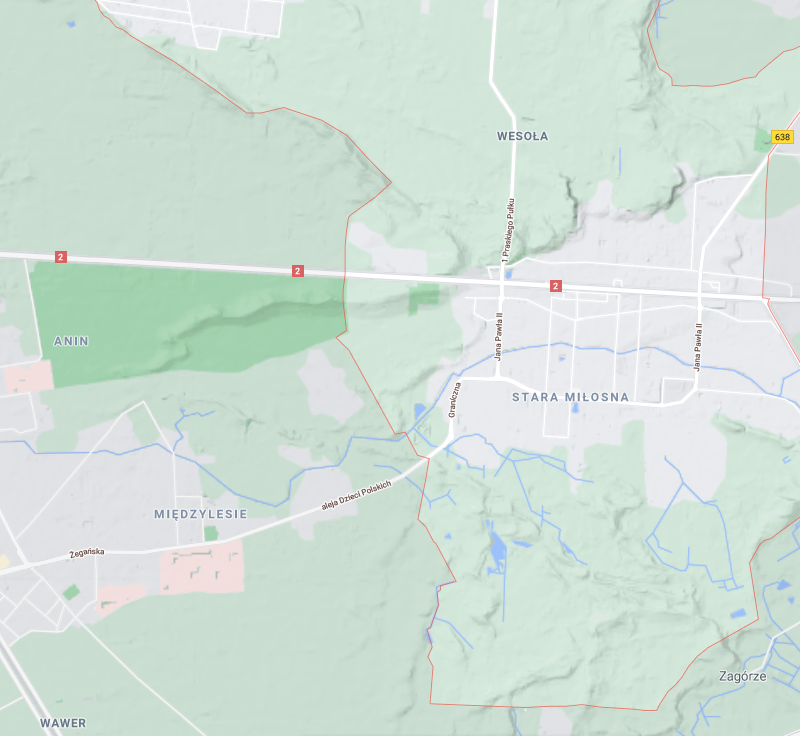

Our project is based in Warsaw. Our topic lies within the field of Habsburg history. This is somewhat atypical, as in our part of Europe the Austrian Monarchy is usually studied by scholars affiliated with institutions located within its old borders. In Ukraine, you will find most Habsburg historians in Lviv, not in Kyiv. In Italy, they will work in Triest rather than in Rome. In Poland, the bulk of them resides in Kraków, Rzeszów, and Wrocław (the latter has inherited the academic traditions of Polish Lviv). Of course, this rule is not waterproof, but it is the general tendency.

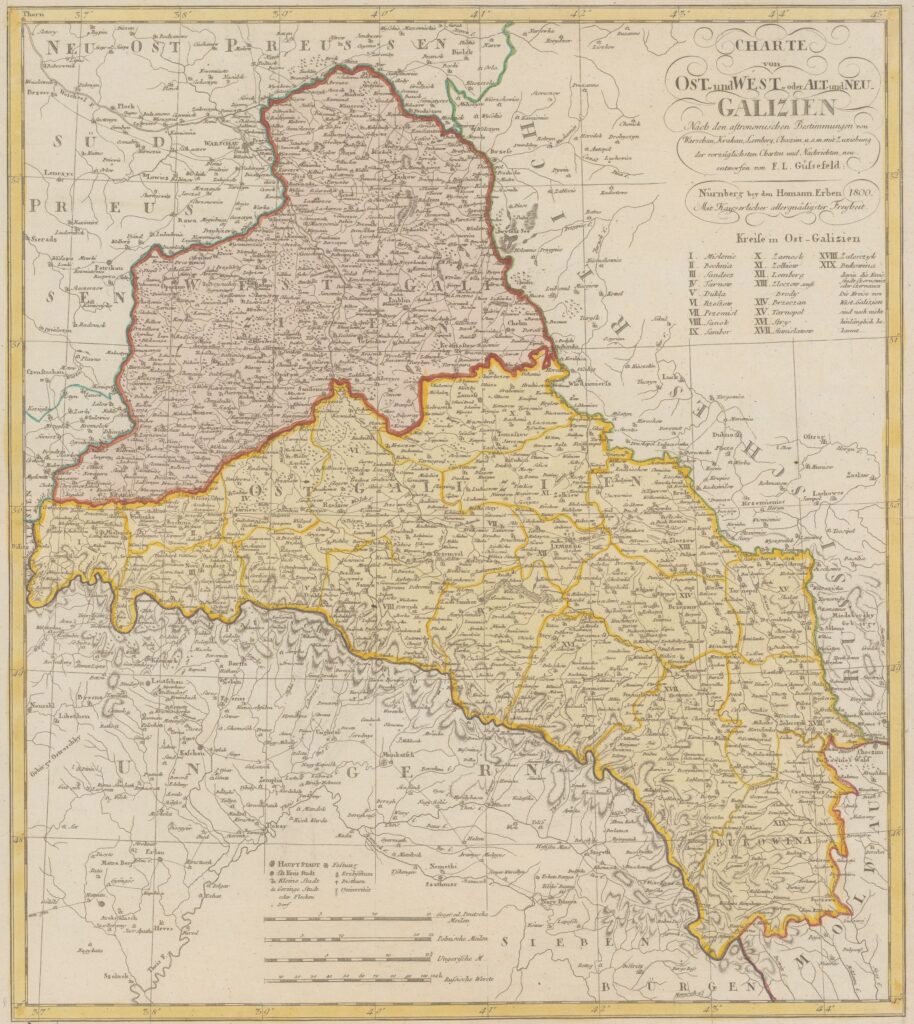

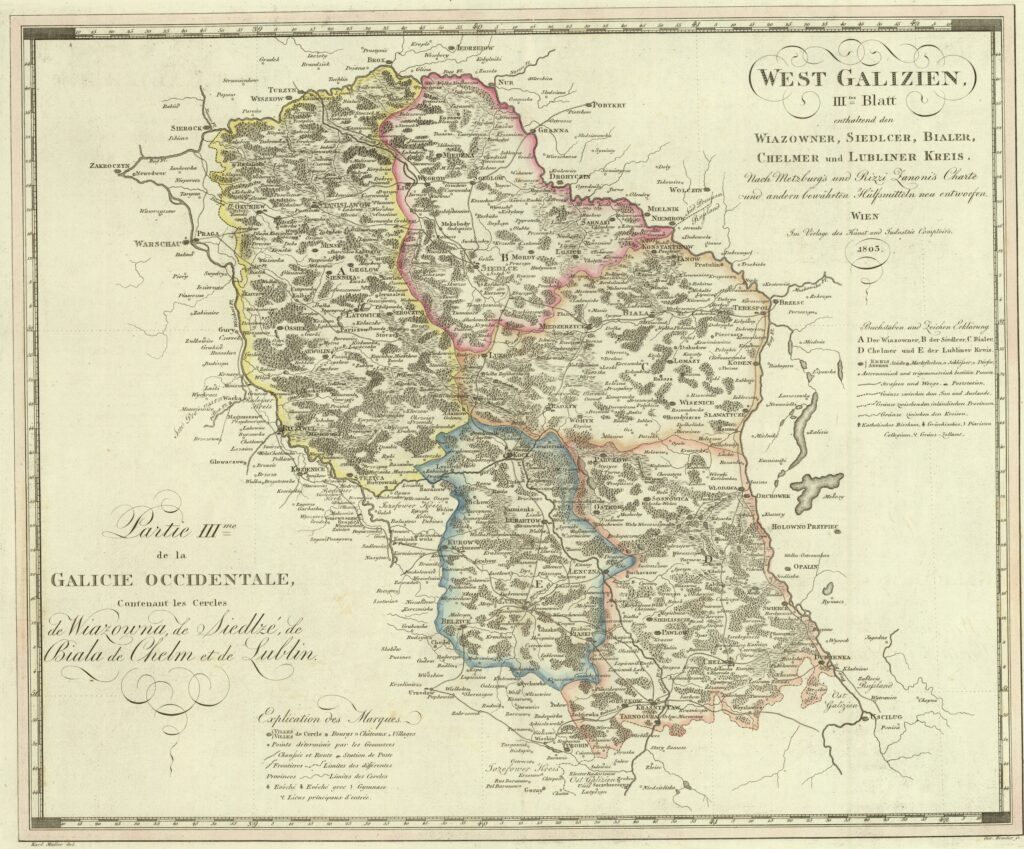

Austrian monarchs have never managed to extend their dominions to Warsaw. But at one point they came very close. In 1795 the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was eventually partitioned and erased from the political map of Europe. Warsaw ended up under Prussian rule, becoming a Kammerdepartment centre in the province named Südpreußen (South Prussia). Its location was quite awkward for administrative purposes, as it lay on the very margins of its territorial jurisdiction. Less than thirty kilometres to the north, on the right bank of the river Bug (Zakhidnyi Buh in Ukrainian), started another Prussian province, Neuostpreußen (New East Prussia). Even more unusually, just a couple of kilometres to the east ran a state border separating the Prussian acquisitions from the Austrian ones, the so-called Westgalizien (West Galicia, sometimes called also Neugalizien). 1 This means, among others, that the first version of the famed Austrian Allgemeines bürgerliches Gesetzbuch was tested in the God-forsaken villages on the eastern outskirts of Warsaw long before it eventually came into force in Vienna. 2

This arrangement did not last long: in 1807 Napoleon defeated Prussia and took the Süd- and Neuostpreußen from it, creating there his puppet Duchy of Warsaw (with the subservient king of Saxony as its duke). But the Austrian border stayed in place, so the newly independent duchy had its eponymous capital just a short walk from the dominions of a hostile power. Two years later, in 1809, Napoleon defeated Austria in the war of the fifth coalition and awarded Westgalizien to his Polish satellite, thus ending Warsaw’s stint as a border town and Austria’s neighbour. After Napoleon’s defeat Westgalizien was never restored to the Monarchy. Instead, the Congress of Vienna chose to transform the Duchy of Warsaw into a non-sovereign Kingdom of Poland, conjoined with the Russian Empire. Pushed back some two hundred kilometres to the south of the Polish capital by Napoleon, Austrian borders remained there for over a century.

At the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Warsaw was a few kilometres away from the borderline, but since then the city limits have been gradually expanding (last changes took place only in the twenty-first century) and now a large section of the Austro-Prussian border cuts through the urban territory. Apart from Warsaw, there is only one other capital in Europe with a historical state border of the Austrian Monarchy running through it: it is Belgrade whose north-western district of Zemun (Semlin in German) used to be an Austrian border town, separated from the Serbian city by the river Sava. 3

Nowadays, on the eastern outskirts of Warsaw there are no easily discernible vestiges of the eighteenth-century Austrian presence. You will not find border stones with imperial eagles or anything like that: this boundary has been erased and forgotten. In the neighbourhood of Zielona, district of Wesoła, there used to be a neoclassicist building of the Austrian customs house, but it was demolished in 1944 by the German military (a paradox of sorts or perhaps not at all). 4

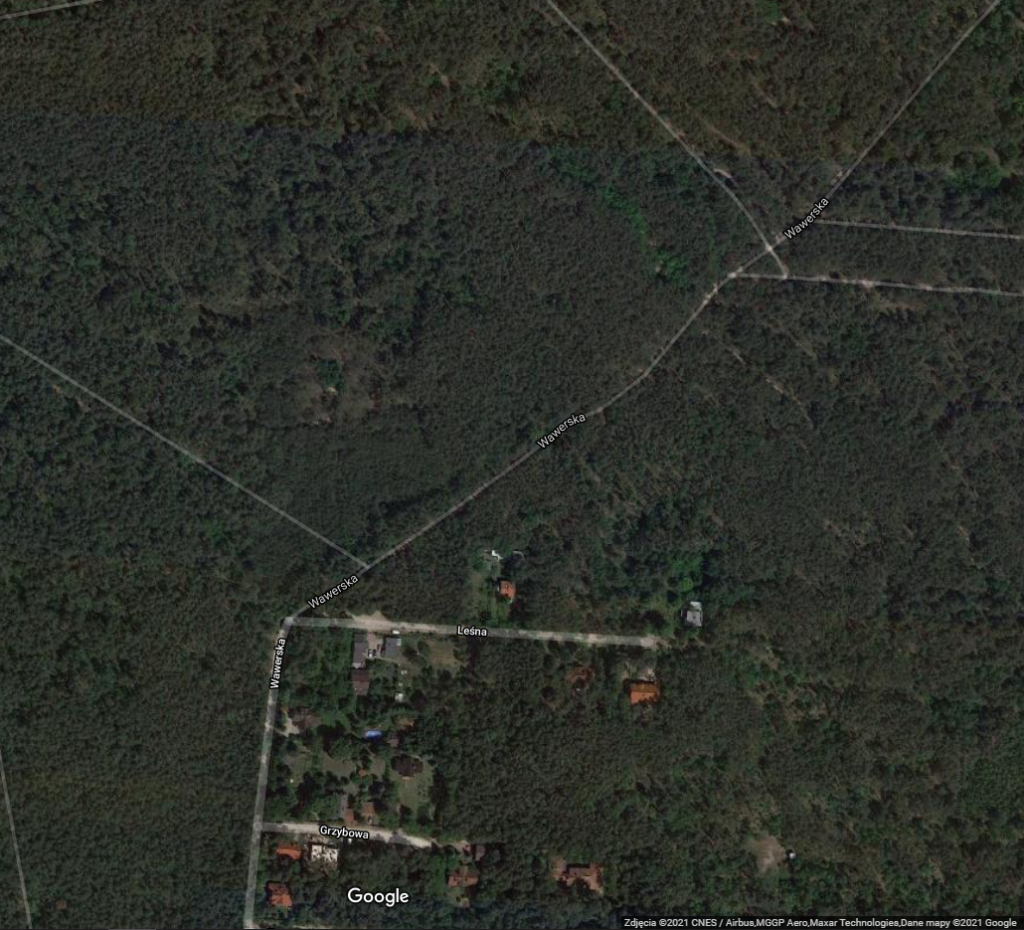

Although it is just a fifteen-minute ride by urban train from downtown Warsaw, tourists never visit this part of the city, devastated by the post-1989 urbanistic laissez-faire. It is, however, dotted with nice patches of woods, remnants of the forests that surrounded Warsaw at the time of the Austrian presence. Today, they attract young families seeking destinations for undemanding weekend walks. In one of such woods you may find the Wawerska street, an unassuming forest road.

As it happens, this dirt road sets the boundary between two districts of Warsaw: Wawer and Wesoła. The district border in this area takes the shape of an acute bend.

The district of Wesoła is composed of several neighbourhoods that used to be separate villages: the eponymous Wesoła, Zielona (the one where the customs house stood until 1944), Wola Grzybowska, and Miłosna, the oldest of all. They all lay on the Austrian side of the border. To the northwest of Miłosna the Austro-Prussian border made an acute bend, just like the one we know from today’s boundary between Wawer and Wesoła.

Now, I am not a land surveyor and I have not combed the archives for the Austro-Prussian delimitation protocols, but the two borders match each other closely and the present-day neighbourhoods should have inherited their boundaries from previous periods. Miłosna was the last locality on the Austrian side, so the western border of its grounds would have coincided with that of the Monarchy. It seems reasonable to assume that today’s western limit of the neighbourhood of Stara Miłosna, the unpaved Wawerska street, is the continuation of the eighteenth-century Austrian border. If you happen to be in Warsaw and you love Austrian history, you should not miss this place. Especially, when it is covered in snow. 5

⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻

1 See also this useful blog post in Polish: http://fenomenwarszawy.blogspot.com/2012/09/warszawa-miasto-nadgraniczne-cz-1.html (last retrieved 14 February 2021).

2 Austrian Allgemeines Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch was published in 1811. Its draft version was enacted in Neugalizien in 1797 as Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch von Westgalizien (published also in Polish as Ustawy cywilne dla Galicji Zachodniej) and extended to Altgalizien the following year.

3 I translate here the Austrian term Kreis, denoting a relatively small territorial unit, as district. I also use this English word for the Serbian gradska opština and the Polish dzielnica, a larger administrative division within the city, nowadays managed by locally elected officials (similar to the German Stadtbezirk and the French arrodissement). Neighbourhood stands for the Polish osiedle, a smaller area within the dzielnica.

4 The Austrian customs house is mentioned on the official website of the Wesoła district authorities: http://www.wesola.waw.pl/strona/historia (last retrieved 14 February 2021).

5 Avid early modernists may remember yet another episode when the Habsburgs came close to ruling over Warsaw. In 1587 a large part of the Polish-Lithuanian nobility elected Archduke Maximilian III of Austria as king. The other party, led by Chancellor Jan Zamoyski, supported Prince Stephen Báthory of Transylvania. The two sides fought a brief civil war which ended with the victory of the Zamoyski’s faction. Had Maximilian been more successful, he would have become an elective king for life, but even then the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth would have remained a separate polity, not a part of the Habsburg inheritance.

⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻

This is not an academic text sensu stricto. Its goal is to disseminate knowledge and to stimulate public interest in our field. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of either PAN or NCN.

Check out the new issue of Acta Poloniae Historica for Tomasz Hen-Konarski’s extensive review of Volodymyr Sklokin’s study of the first autonomous region stripped of its privileges by Catherine the Great.

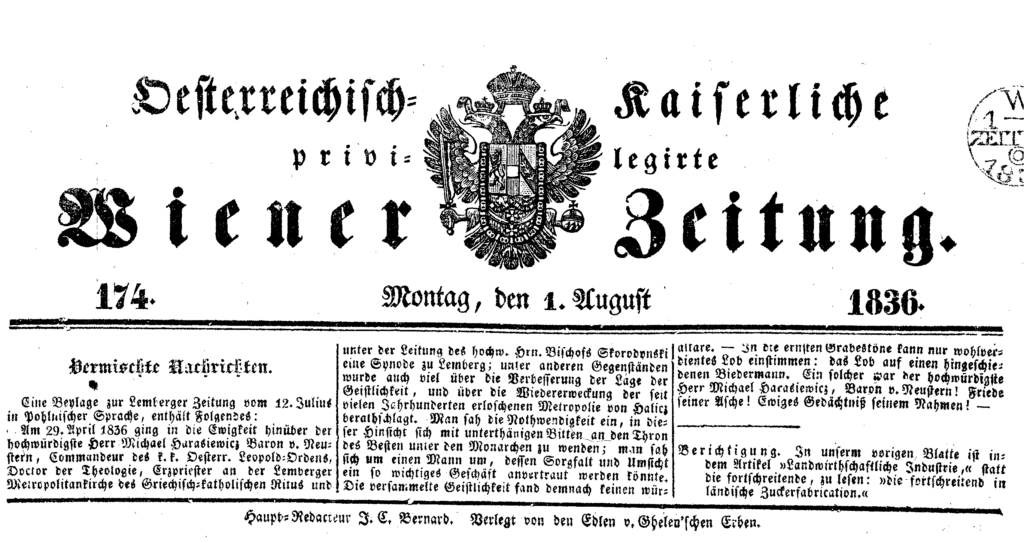

Visit our blog to read an obituary of Mykhailo Harasevych published in 1836 in Lviv and Vienna.

We post this tentative translation of Harasevych’s obituary, not only because it offers a relatively comprehensive narrative of his life, but also because it allows you to see how the account of his career could be interpreted and instrumentalised for political purposes. According to Amvrozii Androkhovych, the author of the text was Hryhorii Iakhymovych, who might have been Baron von Neustern’s relative (Iakhymovych’s mother was de domo Harasevych, but this surname is quite common). In any case, his career resembled that of Harasevych himself in many ways: after studying in Vienna he became a lecturer at the University of Lviv and a canon at the Greek Catholic cathedral chapter there. During the revolution of 1848 he was the unquestioned leader of the conservative wing of the Ruthenian national movement. The crowning moment of his career came in 1860, when after a longer spell in Przemyśl he became the metropolitan of Galicia. 1

The text of this obituary suggests that as early as 1836 a conservative career priest of the kind of Iakhymovych could consistently appeal to the notion of a separate Ruthenian nation to legitimise the politics of his milieu. Whether this was sincere or not is of secondary importance. What remains sadly overlooked in the historiography is the fact that the liberal populists bent on the cultivation of the Ruthenian vernacular, people like Mykola Ustyianovych, Markiian Shashkevych, or Iakiv Holovatsʹkyi, were not the only claimants to introduce the talk of the ancient Ruthenian nation to the Austrian public sphere.

*

»A Polish-language supplement to the Lemberger Zeitung of 12 July contains the following: 2

On 29 April 1836, in the seventy-third year of his life Herr Michael Harasiewicz, Baron von Neustern, commander of the Austrian Imperial-Royal Order of Leopold, doctor of theology, archpriest at the metropolitan church of the Greek Catholic rite in Lemberg and provost of the cathedral chapter crossed the threshold of eternity; he was a man of high intellectual gifts, extensive knowledge, and remarkable services to the state and Church, an edifying priest, an eager teacher, the pride and the glory of the Ruthenian Galician nation. 3

We shall attempt a brief sketch of his life and fame, in order to pay due homage to the noble shadows of so celebrated a man, but also to provide our compatriots with a model of how highly one can elevate himself to achieve dignities through virtue, learning, and service under the just sceptre of the Sublime Monarch of the Austrian Empire.

The most reverend Herr Michael Harasiewicz was born on 23 May 1763 in Jachtorow of the Zloczow district: his father Gregor was a parish priest there of the Greek Catholic rite. The fortune of the Ruthenian parish priests was in no way enviable before the return of Galicia to the Imperial House of Austria. 4 Reduced to rely on the yields from a piece of arable land, which they were forced to work by the sweat of their brow, and on the meagre support of their poor parishioners, struggling incessantly with want of every sort, they were not able to either give their children an appropriate upbringing or to support them on their further career path. However, with the help of a patriarchal way of living, piety, and domestic virtues, they succeeded in inculcating in their children the fear of God, industriousness, and devotion to the legitimate authority ordained by God. Their motto was: Ora et labora.

Having received his first instruction in the Ruthenian language and church services while still a child in his father’s house, the young Michael was sent to the venerable Piarist fathers in Zloczow. Fully convinced that only persistent diligence and self-sacrifice would allow him to advance, he displayed so much talent there that already in the eighteenth year of his life he was deemed fit to enter the Viennese seminary at the church of Saint Barbara, where the government, with its fatherly preoccupation to secure excellent pastoral ministry, offered funding to educate youths inclined to that vocation. In Vienna, and later in Lemberg, where a general seminary was established, he dedicated all the prowess of his youth to the study of philosophy and theology; this he did with so strong an enthusiasm and such a blessed success that after five years the authorities in question felt compelled to issue him a certificate of his deep learning, manly gravity, and admirable prudence. 5

The government, able to appreciate every talent properly, entrusted him on 1 September 1787, a youth of twenty-four years, who had not yet achieved the priestly dignity, the chair of pastoral theology at the University of Lemberg. Not only the secular authority, but also the spiritual one noticed his outstanding skills, because in the very same year, in recognition of his above-mentioned characteristics, the Lemberg General Consistory appointed him the diocesan examiner with the decree of 30 October 1787. For thirteen years, until 1800, he fulfilled the duties of a full professor. At the same time, as a consequence of an aulic decree of 14 September 1792, he occupied the chair of the Ruthenian-language exegesis to the full satisfaction of the government, of the higher clergy, of the faculty of theology, and of his numerous students.

In the year 1789, on 5 August, after the prescribed examinations, he achieved the title of doctor of theology. In the year 1795 and 1796 he served as dean and representative of the faculty of theology; subsequently as chairman of the college of professors; as associate member, rapporteur, and director of the then existing Galician consessus studiorum, whose dignity he also continued to hold later in his capacity as the vicar general of the archdiocese until the dissolution of that body. 6 Next, as prorector he chaired the academic senate of the Lemberg University in the year 1805, but eventually nominated in the year 1813 as the imperial-royal commissioner for the public examinations, he occupied this distinguished post till the end of his life. This is a short outline of the deceased within the sphere of his public academic activity; his services in his pursuits as priest, citizen, and scholar are no less brilliant and significant.

In the year 1793 he conjoined himself in the sacred union of marriage with Therese of the noble house of Jablonski. And then, having chosen, after a mature reflection, the priestly career, he received the holy orders from the hands of the most reverend Herr Peter Bielanski, Ruthenian bishop of Lemberg and Halicz and imperial-royal privy councillor. Not even two years had passed from his consecration, when he became an honorary canon at the Przemysl cathedral chapter. And three years later with the support of the most reverend Herr Nicolaus Skorodynski, bishop of Lemberg and Halicz, the decree of His Imperial-Royal Apostolic Majesty of 14 August 1800 named him episcopal official and vicar general as well as the first councillor of the consistory. He occupied this post both under that shepherd and under his successor, his excellency the Most Reverend Metropolitan Angellowicz, until the year 1814.

In the year 1803 the clergy of the Lemberg diocese held a synod presided over by the Most Reverend Herr Bishop Skorodynski: among other topics, its participants deliberated upon the improvement of the clergy’s situation and the revival of the metropolitanate of Halicz, which had been abolished centuries ago. For this purpose they needed to submit their supplications at the throne of the Best among the Monarchs and they needed a man to whose diligence and prudence so important an affair could be entrusted. The assembled clergy found no man worthier and better suited for this mission than the Most Reverend Herr Michael Harasiewicz: they elected him by acclamation and on 2 May 1803 invested him with full powers. The bishops present then in Lemberg, Ważynski of Chelm, Angellowicz of Przemysl, and Skorodynski of Lemberg, corroborated this synodal election with a letter of 12 May 1803, empowering him as the envoy of the whole Galician Ruthenian clergy, and sent him to Vienna to submit a supplication.

His tireless zeal and manifold efforts were crowned with the desired success. The Gracious Monarch received the supplications from the clergy of the Ruthenian nation with a fatherly pity. Three years later the old metropolitanate of Halicz was established and obtained a celebrated head. It is well known to the clergy and to the whole Ruthenian nation how much the late Most Reverend Herr Michael Harasiewicz contributed with his efforts and counsels to the achievement of this lofty goal. 7

When eventually the Most Serene Lord, with the diploma of 25 February 1813, had mercifully ordered the erection of the lapsed chapter at the Lemberg cathedral, this meritorious man, twice a diocesan administrator in spiritualibus and temporalibus (first after the death of the Most Reverend Herr Bishop Skorodynski and later after the passing away of His Excellency the Metropolitan Angellowicz), was nominated with an aulic decree of 3 June 1813 to serve as archpriest or provost, that is the first prelate of the chapter. The deceased remained in this post with an unshakable enthusiasm to the last moment of his eventful life. 8

By no means did this blessed prelate limit himself to perfecting only those fields of knowledge that his vocation required of him; he spent all his life studying, devoted wholly to learning. Already a full professor of pastoral theology, he attended the lectures on law at the Lemberg University and subjected himself to the prescribed examination, in order to achieve a doctorate also in that faculty. In the years 1794, 1795, 1796, and 1797 he was the chief editor of the first periodical in Lemberg under the title Dziennik Patriotycznych Polityków (Journal of Patriotic Politicians). 9 Along with the duties resulting from his elevated position, he spent his old age researching the history of his fatherland and he wrote down a rich hoard of news and events for the history of Galicia. It was he who, upon the request of the Apostolic Nunciature, provided a comprehensive description of the Ruthenian hierarchy of the Greek Catholic rite. He enriched German magazines with valuable studies and his literary efforts always stood out for their deep learning, intellectual fertility, and mature wisdom. 10

So many manifold services in the sphere of learning and priesthood as well as the proofs shown in 1809 of an impeccable loyalty, of an unshakable constancy, and of an unlimited devotion to the legitimate throne and the Most Serene Ruler — all this could not escape the notice of the just government that knows how to appreciate and reward every merit. 11 On 13 December 1810 the Most Serene Emperor Francis I distinguished him with the honourable award of the commander cross of the Imperial Order of Leopold, to which a personal annual allowance of 800 florins was attached; and on 11 April 1811 he ennobled him together with his legitimate progeny as a baron of the Empire with the title “von Neustern”. As a result of this sublime grace in the year 1817 he was immatriculated in the estates of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria and he repeatedly sat on the diets as deputy of the metropolitan chapter.

This is a concise biographical sketch of a man of unusually virtuous conduct and rare learning. Rather than a hired quill it is the genuine admiration that draws it, to which one is irresistibly forced by true services and outstanding merits. A bright and alert mind; a mature judgment, trained through dignified knowledge and a deep experience; religion allied with philosophy: these are the flowers with which he plaited himself a wreath of immortal glory among his compatriots. His glory and recollection will fly through centuries.

The sheer number of people of different social standings, including all the illustrious men, gathered at his funeral service, has clearly demonstrated this all-pervasive admiration for him. The clergy expressed its love in a Ruthenian elegy, both emotionally touching and genuine in its popular spirit. The students of the Lemberg Ruthenian Seminary had it printed by the Stauropegion Press and distributed it at his burial. 12 An echo of the mourning caused by so painful a loss reverberated also on the banks of the Danube, where the young clerics of the Ruthenian nation at the Viennese Imperial-Royal City College immortalised the memory of the celebrated Sage in yet another dirge printed by the Mekhitarist fathers. 13

Incensed altars of the flatterers fume only for the living. The serious funeral music can convey but a fully deserved praise: the praise for an honest man. This was the Most Reverend Herr Michael Harasiewicz, baron von Neustern! Peace to his ashes! Eternal glory to his name!«

⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻

1 For a summary of Mykhailo Harasevych’s life see Amvrozii Androkhovych, “Lʹvivsʹke »Studium Ruthenum«,” Zapysky Naukovoho Tovarystva imeni Shevchenka, Vol. 146 (1927), 68-75. That the maiden name of Hryhorii Iakhymovych’s mother was Harasevych is mentioned in V. Haiuk et al., Halytsʹki mytropolyty (Lviv, 1992), 37.

2 This translation is based on the German-language version published in the Wiener Zeitung. I have not been able to consult the Polish-language original. I tried to follow the text with its characteristic syntax as closely as possible, but had to take some liberties, in order to render it understandable in English. Here I want to thank Jared Warren for language assistance.

3 On this website we tend to render the names of individuals in present-day standard Ukrainian (simplified LoC romanisation). However, in this translation I leave the forms as they stand in the primary source, hence Michael Harasiewicz instead of Mykhailo Harasevych, Angellowicz instead of Anhelovych, and so on. Likewise, although we usually give place names in accordance with their current administrative status, here I give the toponyms as printed in the obituary, hence Lemberg instead of Lviv, Jachtorow instead of Iaktoriv, Zloczow instead of Zolochiv, and so on. Characteristic inconsistencies in the use of diacritics have been preserved.

4 In 1772.

5 The so-called Barbareum was an elite Greek Catholic seminary established in Vienna by the government of Maria Theresa in 1774 and closed down after ten years, when Joseph II replaced it with the Greek Catholic General Seminary in Lviv. In 1803 a college for the Greek Catholic clerics at the University of Vienna was reopened on the premises of the old Barabareum. See Amvrozii Androkhovych’s “Vidensʹke Barbareum. Istoriia korolivsʹkoi Generalʹnoi hreko-katolytsʹkoi Semynarii pry tserkvi sv. Varvary u Vidni z pershoho periodu ii isnuvannia (1775-1784),” in Iosyf Slipyi, ed., Pratsi Hreko-Katolytsʹkoi Bohoslovsʹkoi Akademii u Lʹvovi. T. I-II (Lviv, 1935), 42-113.

6 In the autumn of 1790 the government of Leopold II decreed the so-called consessus studiorum (ławica akademicka in Polish, Studien-Consess in German), an intermediary entity responsible for the management of education in Galicia. Consessus studiorum was designed as a sort of representative assembly composed of the deputies of university faculties and secondary schools. The first consessus gathered only in 1792. After ten years the government of Francis II terminated this experiment in educational self-government. See Ludwik Finkel and Stanisław Starzyński, Historya Uniwersytetu Lwowskiego (Lviv, 1894), 145-152.

7 For the most up-to-date account of the establishment of the Galician Metropolitanate see Vadym Adadurov’s introductory articles to his two collections of primary sources: Fundatsiia Halytsʹkoi Mytropolii u svitli dyplomatychnoho lystuvannia Avstrii ta Sviatoho Prestolu 1807-1808 rokiv: zbirnyk dokumentiv (Lviv, 2011) and Podil Kyivsʹkoi ta pidnesennia Halytsʹkoi uniinykh metropolii: Dokumenty ta materiialy vatykansʹkykh arkhiviv (1802-1808 roky). Uporiadkuvannia, vstup i komentari Vadyma Adadurova (Lviv, 2019).

8 The establishment of the Lviv cathedral chapter was one of the main concerns of the Greek Catholic secular clergy in the first four decades of the Austrian rule over Galicia. For this topic see Antoni Korczok, Die griechisch-katholische Kirche in Galizien (Leipzig, 1921), 56-66 and Iuliian Pelesh, Geschichte der Union der ruthenischen Kirche mit Rom von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart. Bd. 2, Von der Wiederstellung der Union mit Rom bis auf die Gegenwart (1598-1879) (Vienna, 1880), 612-634.

9 Dziennik Patriotycznych Polityków was not the first periodical in Galicia but the first Polish-language daily of the Crownland. Most of its content was political news. The authors tried to balance their sympathy for the Polish-Lithuanian Enlightenment with the loyalty to the Austrian government. Mykhailo Harasevych was the responsible editor of the daily, but the extent of his actual involvement remains unclear. See Maurycy Dzieduszycki, “Przeszłowieczny dziennik lwowski,” Przewodnik Naukowy i Literacki, Year 3 (1875), 33-51 and Halina Kozłowska, “Lwowski »Dziennik Patriotycznych Polityków« (1792-1798),” Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Prace Historyczne, No 55 (1976), 79-111.

10 See for example his “Berichtigung der Umrisse zu einer Geschichte des religiösen und hierarchischen Zustandes der Ruthener, in den Nrn. 52, 53, 54, 56, 57 und 58. Von einem griech. kathol. Domkapitularen,” serialised in 1835 in the Ergänzungsblätter zur Oesterreichischen Zeitschrift für Geschichts- und Staatskunde. This was a critical response to an article by Mykhailo Malynovsʹkyi.

11 In 1809, in the course of the war of the fifth coalition, the army of the Napoleonic Duchy of Warsaw occupied Galicia. The interim military government sequestrated the property of the Greek Catholic church leaders and pressured them to actively support France against Austria. Unwilling to comply, Anhelovych and Harasevych attempted to flee across the Carpathians, but they were intercepted in the village of Senechiv near the Hungarian border. Ultimately, this part of Galicia remained under Austrian rule and the whole episode worked to the advantage of the Greek Catholic leadership, as it testified to their loyalty to the Habsburg emperor. See Mykhailo Harasevych, Annales Ecclesiae Ruthenae, 919- 934 and Pelesh, Geschichte der Union. Bd. 2, 875-881.

12 The Ruthenian elegy, “eben so volksthümlich als rührend”, must be Mykola Ustyianovych’s Sleza na grobe Ego Vysokoprepodobie i Vsechestniishago Gospodina Mikhaila Barona ot Neustern Garasevicha (for this particular title, heavily saturated with old Cyrillic characters, I use the simplified LoC romanisation of Church Slavonic). Written in Galician Ruthenian vernacular, it was printed by the press of the Stauropegion Institute, created by Joseph II on the basis of the early modern Lviv Dormition Brotherhood.

13 I have not been able to identify the other piece mentioned in this paragraph. The printing house responsible for its release belongs the Mekhitarists, a congregation of Armenian Catholic monks. They have two principal houses: one on the island of San Lazzaro in Venice, the other in Vienna.

⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻

This is not an academic text sensu stricto. Its goal is to disseminate knowledge and to stimulate public interest in our field. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of either PAN or NCN.