We post here an allegorical article on the French Revolution published in September 1792 in a Polish-language political journal from Lviv.

In the 1790s Mykhailo Harasevych, the patron saint of this research project, was involved in the publication of Galicia’s first political daily, the Dziennik Patriotycznych Polityków (Journal of Patriotic Politicians, henceforth DPP), allegedly a mouthpiece of the eponymous Towarzystwo Patriotycznych Polityków (Society of Patriotic Politicians). 1 Of the latter we know close to nothing (were they really a group of people or just a literary device?). The exact scope and nature of Harasevych’s contribution is yet to be ascertained, but it seems justifiable to assume that the ideological positions presented by the anonymous author(s) of this paper could not be very far from his own at that time. In any case, articles in the DPP show us what Galician elites knew about and understood from the European politics of the Age of Revolution and how they positioned themselves in regard to them as both the Austrian subjects and the former citizens of the still existing Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. 2 I have resolved to translate some interesting excerpts from the DPP as an illustration of the ideological horizon of Galician elites, be they Greek or Latin Catholic.

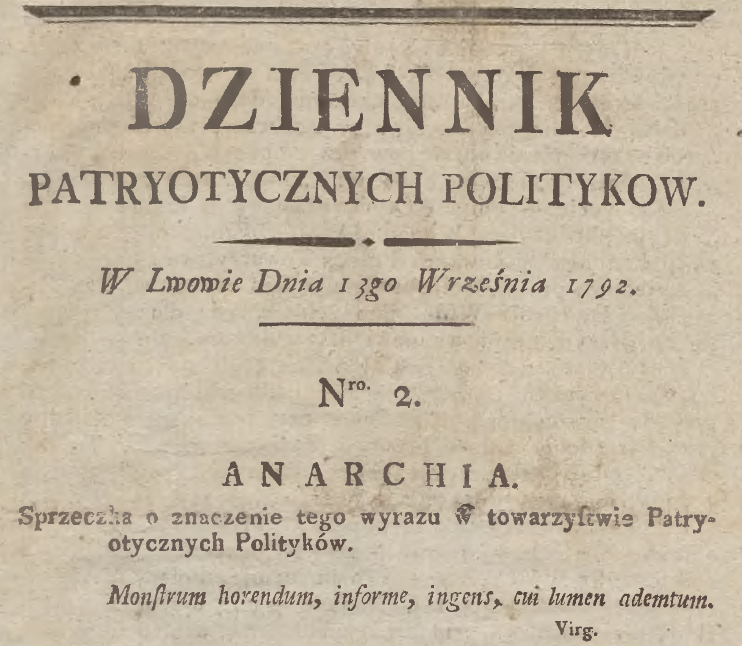

In the second issue of the DPP, released on September 13, 1792, we find an allegorical essay on anarchy, introduced as a discussion that allegedly took place at a meeting of the Society of Patriotic Politicians. The subject of anarchy was especially relevant in the early 1790s, as many enlightened Europeans observed the violent breakdown of the French monarchy with horror. Indeed, the very first issue of the DPP related in detail la journée du 10 août, when the republican fédérés stormed the Tuileries Palace, effectively ending the royal power. 3 However, the author of the DPP essay on anarchy chooses to articulate his reflection in a bipolar field. Along the rather obvious French context, the other crucial point of reference is the political scene of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: the conflict over the May Constitution of 1791 ending with Russian intervention and the creation of a reactionary government dominated by the so-called Targowica Confederation. 4

The text contains several interesting moments, but I would only like to draw readers’ attention to three points here. First of all, the participants in the discussion related in the essay do not hesitate to identify the inhabitants of Poland-Lithuania as their compatriots (Polish współziomkowie), yet they do not reveal any sense of special solidarity resulting from this fact. Although the Patriotic Politicians are visibly concerned about the fate of the Commonwealth, one can also sense a sort of satisfaction at Galicia’s splendid isolation from the chaotic Polish-Lithuanian factionalism. Secondly, the critique of the violence and instability allegedly inherent in republican politics, be it French or Polish-Lithuanian, is completely divorced from Catholic orthodoxy. 5 Some images seem to be inspired by the apocalyptic visions of the Francophone Counter-Enlightenment, but others come from the Masonic repertoire. As a whole, the argumentation in the essay is purely pragmatic and secular (or deistic, to be precise). The authors of the DPP do not align themselves with the radical enemies of the Revolution, but rather assume the position of a moderate conservative Enlightenment, not unlike the luminaries of the Austrian legalistic monarchism such as Leopold II himself, Joseph von Sonnenfels, or Karl Anton von Martini. 6 Lastly, it is striking that the authors’ political concerns are so much in line with those of their contemporaries from other parts of Europe. If not for the explicit references to Poland-Lithuania, one might not guess that this text was written and published in a country located to the east of the river Elbe. There is nothing fundamentally East European about its form and content.

Galician Patriotic Politicians prove to be keen observers of the European politics. They successfully synthesise their knowledge of Western and Eastern European developments into a coherent, if not very original, diagnosis of contemporary ideological conflicts. English civil wars, the French Revolution, May Constitution, and the Targowica Confederation are presented as items of the same series that could be captioned ‘republican disorders’. In this way, the Patriotic Politicians define their own location in a Lviv suspended between Paris, Vienna, and Warsaw. One cannot resist noticing that they seem to be quite satisfied that the House of Austria potects their Galician patria from the vicissitudes of republican factionalism. Here, we can see how a section of the Enlightened Polish-speaking elite of that Habsburg crownland, a country just twenty-years old at the moment, comes to terms with the dynamic realities of their time and thus contributes to the collective effort of inventing Galicia, a process analysed among others by Larry Wolff and Miloš Řezník. 7

*

ANARCHY

A quarrel over the meaning of this word in the Society of Patriotic Politicians

Monstrum horendum, informe, ingens, cui lumen ademtum.

Virg. 8

As is widely known, in accordance with the regulations adopted once and for all in our society, each member cum voce activa is responsible for one kingdom and has to faithfully gather news from that state, add his remarks, and pronounce his opinion during sessions in pleno, after which everybody is allowed to reveal their thoughts and say whatever they like. 9

When the reading of news at our last session was over, Mr. Zawieruchowski, 10 rapporteur of tidings from Poland, rose and spoke from the depths of his heart:

‘Thank God that peace has been restored in Poland. The way in which the unrest was quelled was onerous indeed, but as there was no other, they had to resort to this one. It is enough that the country is peaceful, that the war is over.’ 11

‘I am happy for you, sir,’ responded Mr. Mędrski, the serious president of our society, 12 ‘but I am still concerned about the future.’

‘But why?’ said Mr. Zawieruchowski. ‘Do you, sir, want the war to last longer?’

‘I despise the spilling of innocent blood, but…’

‘What are you afraid then? And what is the cause of your fear?’

‘Knowing how restless the minds of our compatriots are, do not I have legitimate reasons for concern about the future?’

‘It has always been this way: dilemmas, dissensions, hatreds often prove beneficial for a free country. Otherwise, would the Englishmen have brought their affairs to the present state?’

‘English history is full of dreadful periods. Moreover, do you deem, gentlemen, that Poles are Englishmen?’ 13

‘Why not? But this is a topic for another occasion. Now, sir, please tell us why you fear about the future.’

‘This is why: the sympathisers of the May 3 Constitution have not abandoned their hopes. Gentlemen, you heard recently that the number of the discontented is substantial and that the Friends of the Constitution will find supporters and backing for their endeavours.’ 14

‘So what?’

‘The General Confederation and its Protectress will not make any concessions.’ 15

‘What then?’

‘A civil war.’

‘And the outcome?’

‘The lot of Poland is pretty similar to that of France: anarchy! Oh, my beloved gentlemen, this word is dreadful, but its consequences are even worse: disgusting devastations!’

‘Please instruct me what this anarchy means. I hear this word a lot, but each person explains it in a different way.’

‘Sir, think about France and you will have a vivid representation of anarchy. All civic bonds are torn, government – toppled, laws – disrespected. Superiors are powerless, courts of law – deprived of authority, virtuous citizens – either murdered or moaning in dungeons, government – in the hands of the dissolute populace. A couple of days ago, after having read a lot about the current revolution in France, I fell soundly asleep and just before the dawn I had the following dream, as if I had been awake:

DREAM

I was near Paris, on Montmartre hill. 16 The land was covered in thick darkness and there was no light except for the moon beams. Suddenly, I noticed some divine figure approaching me from the east. It was adorned with brightness and the whole world was depicted on its vestments. From its pleasant face I recognised that this was Oromazdes (principium boni) floating on clouds above the unfortunate France. 17 When he came closer, I heard these words come out from his mouth: “The French nation is numerous, manly, industrious, and valiant, but lest it waste these rare gifts, I shall create a powerful genius to watch over its prosperity.” Then, he said: “Let it be so!” and immediately a female figure of such beauty appeared that I had never before seen an equal. Then, he took from the mass of farmers, artisans, and merchants and used this material to mould this woman’s breasts, which produced ambrosia instead of milk. Next, he took from the mass of learned men, statesmen, lawyers, and sages and having created a brain out of it he put it in her head, after which her eyes started to radiate with bright rays. Eventually, he took from the mass of kings and put it right in the middle of her brain saying: “This will be the centre where all the powers animating the limbs meet.” Immediately, the goddess began to move and act as a protectress of France. Oromazdes flew towards the west and I prostrated myself, piously adoring the omnipotence of gods.

Then, having heard the murmur of thunders in the distant north, I bounced to my feet. Again, there was a thick darkness interrupted by occasional lightnings. Trembling with fear I recognised the approach of Ahriman (principium mali), thunderbolts still in his hand. 18 “Hah,” he shouted in a tremendous voice. “The destroyer of my projects, that friend of good order, was here. I can see the traces of his actions. You, woman, are a work of his hands. True, you are powerful, but you will not be stronger than I am. Become what I want you to be!” Having said that, he threw a thunderbolt with his right hand and hit her right in her head: her eyes dimmed, her brain leaked, her breasts dried, and her limbs fell off. The whole body melted into an amorphous lump, which, too feeble to stand on its own, fell upon France. Her breasts teemed with worms and vipers; spears, swords, and daggers punctured her belly; and terrifying flames gushed from her intestines as if from a bottomless abyss. Having concluded this terrible work, Ahriman roared in the air: “Anarchy!” and flew back towards the north, whereas the terror woke me up.’

The whole society agreed to publish this dream in our journal. 19

⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻

1 See Maurycy Dzieduszycki, “Przeszłowieczny dziennik lwowski,” Przewodnik Naukowy i Literacki, Year 3 (1875), 33-51 and Halina Kozłowska, “Lwowski »Dziennik Patriotycznych Polityków« (1792-1798),” Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Prace Historyczne, No 55 (1976), 79-111.

2 Galicia was created as a result of the first partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772. The latter survived as a separate polity until the third partition in 1795. For 23 years the Commonwealth was Galicia’s northern neighbour and many noble landowners would have their land estates on both sides of the border as the so called sujets mixtes with the right to vote in the diets of both countries.

3 On August 2, 1792, radical republican militants, mostly the federés volunteers, stormed the Tuileries Palace, the Parisian residence of the royal family. This event resulted in the de facto end of constitutional monarchy in France (although the Republic was not officially proclaimed until the second half of September). In the following month French political scene became especially brutal and volatile, which is sometimes characterised as the First Terror. These events were widely publicised all over Europe, usually in a negative light.

4 In the eighteenth century the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth languished under Russian protectorate, as St Petersburg blocked any attempts at substantial political reform. The situation changed in 1787, when the Ottoman Empire declared war against Russia. Forced to focus on the military actions in the Black Sea region, Empress Catherine II was no longer able to control the Polish-Lithuanian politics so closely. As a result, years 1788-1792 saw intense political reforms in Poland-Lithuania, culminating with the Enlightened Constitution of May 3, 1791. However, many conservative republicans were unhappy with the new form of government: they deemed that it deprived them of their liberties for the sake of orderly administration. These malcontents formed in 1792 an oppositional union which went down in history as the Confederation of Targowica, named so after the town of Torhovytsia in central Ukraine, where its manifesto was allegedly penned and published. At the same time, Catherine signed a satisfactory peace treaty with the Ottomans and directed her gaze towards the Commonwealth. Thus, the Targowica leaders obtained the Russian military support necessary to overthrow the reformist government in Warsaw. The Russian invasion in the summer of 1792 brought an abrupt end to the period of Enlightened reform in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and accelerated the eventual collapse of this polity. The name of Targowica remains a byword for high treason in contemporary Polish.

5 For the Counter-Enlightenment see Darrin McMahon, Enemies of the Enlightenment: The French Counter-Enlightenment and the Making of Modernity (Oxford, 2001) and Martyna Deszczyńska, Polskie kontroświecenie (Warsaw, 2011).

6 See Teodora Shek Bernardić, “Modalities Of Enlightened Monarchical Patriotism In The Mid-Eighteenth Century Habsburg Monarchy,” in Balazs Trencsenyi and Márton Zászkaliczky, eds, Whose Love of Which Country? Composite States, National Histories and Patriotic Discourses in Early Modern East Central Europe (Leiden, 2010), 629-661.

7 Miloš Řezník, Neuorientierung einer Elite: Aristokratie, Ständewesen und Loyalität in Galizien (1772-1795) (Frankfurt am Main, 2016) and Larry Wolff, The Idea of Galicia: History and Fantasy in Habsburg Political Culture (Stanford, 2010).

8 A corrupted quote from Virgil’s Æneid. The correct version is Monstrum horrendum, informe, ingens, cui lumen ademptum, meaning: “A monster frightful, formless, immense, with sight removed.” It is a description of cyclops who were presented as quintessentially irrational and cruel brutes in the Greco-Roman poetry. Here, it serves as a metaphor of mob rule.

9 Cum voce activa literally means “with active suffrage,” but here it is probably intended to describe full suffrage. Sessions in pleno are general meetings, which all the members of the society are encouraged or even required to attend.

10 Mr. Zawieruchowski is a meaningful name derived from the Polish noun zawierucha, meaning storm, turmoil, chaos.

11 At the end of July 1792, in the face of overwhelming Russian might, Poland-Lithuania’s pro-reform king chose to surrender and accept the repeal of the 1791 Constitution. Targowica leaders took up the reins of government and started to persecute their enemies. In 1793, they had to swallow the second partition of the Commonwealth by Prussia and Russia, but until the outbreak of the Kościuszko Uprising in 1794 one could also credit them with providing a modicum of stability.

12 Mr. Mędrski is another meaningful name, this time derived from the Polish adjective mądry, meaning wise.

13 The authors mean here the British Civil Wars of 1638-1652 and the Glorious Revolution of 1688-1691.

14 By Friends of the Constitution the author may mean the members of the Assembly of Friends of the Government Constitution “Let there be Light” (in Polish Zgromadzenie Przyjaciół Konstytucji Rządowej “Fiat Lux”), sometimes credited as the first modern political party in Poland-Lithuania. More broadly, the author can describe in this way any supporters of the 1791 Constitution or in fact any enemies of the Targowica regime established thanks to the Russian invasion of 1792.

15 The General Confederation stands here for Targowica. Obviously, its protectress was the Empress Catherine II of Russia.

16 The hill of Montmartre remained outside the city limits until 1860.

17 In the Zoroastrian tradition Oromazdes (or Ahura Mazda) is the benevolent creator god, lord of wisdom and order, the hypostasis of good, rendered here in Latin as principium boni. Zoroastrian-inspired symbols were present in the Masonic rituals and, as a result, in the wider cultural sphere of the eighteenth-century Europe: see for example Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera Zoroastre (1756) about the struggle of good and evil spirits and their human followers.

18 In the Zoroastrian tradition Ahriman (or Angra Mainyu) is the hypostasis of evil, rendered here in Latin as principium mali, the destructive and chaos-sowing opponent of Oromazdes.

19 I would like to thank Jared Warren for his careful reading of the first draft of this translation and his useful editing suggestions.

⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻⸻

This is not an academic text sensu stricto. Its goal is to disseminate knowledge and to stimulate public interest in our field. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of either PAN or NCN.

One Reply to “Making sense of the French Revolution in Habsburg Eastern Europe”

Comments are closed.